Follow the Signs

Have you noticed the green signs as you walk or drive around Indian Mills? These signs were erected by the historical society over 20 years ago to designate our cultural landmarks. Each sign, located on the original historic site, provides a brief summary of it’s relevance to our past. The map below shows the location of many of the signs and the video provides a great overview of the educational collaboration between IMHS and local schools.

Click here to go directly to a narrative of several historical markers.

This map drawn in 2008 updates the original map from the 1970’s, which only had 24 markers. This new map has all 30 sites, including other sites identified by the township. The map received the Burlington County Board of Freeholders Historic Preservation Recognition Award for Achievement/Leadership. Mr. Catts, our local historian, also received a proclamation from the township for donating a framed copy of the map that hangs in the townships municipal building. There are also framed copies hanging in the library of both township schools.

Recently, the 3rd grade of the Indian Mills school district completed a project where students investigated all of the 30+ historical markers. The video below describes this exciting project which became a endeavor for students and parents alike.

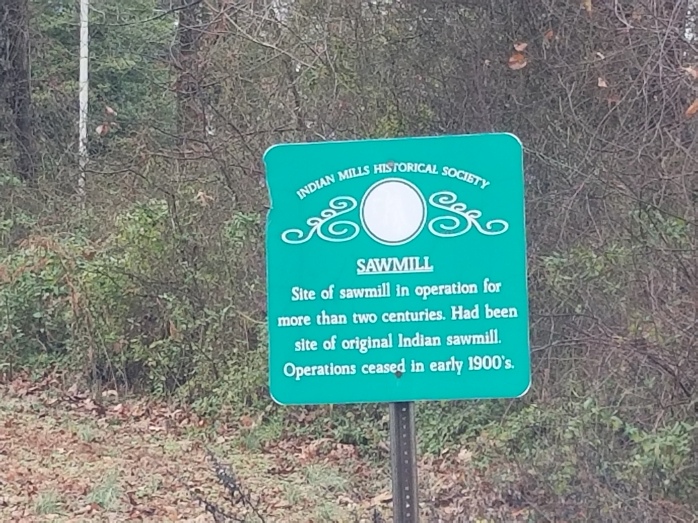

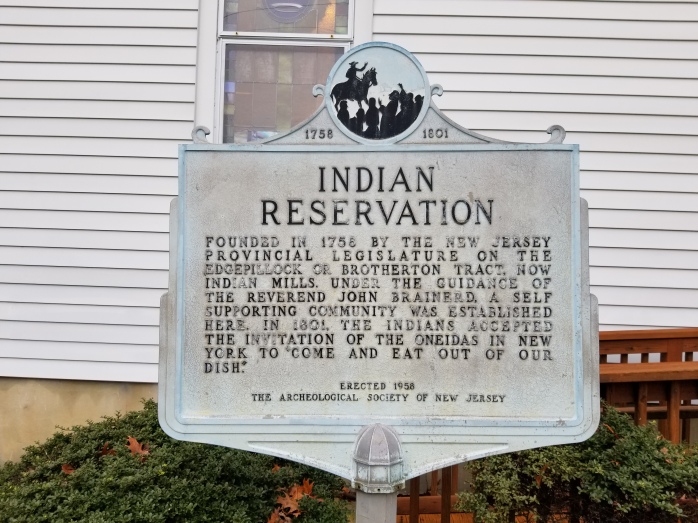

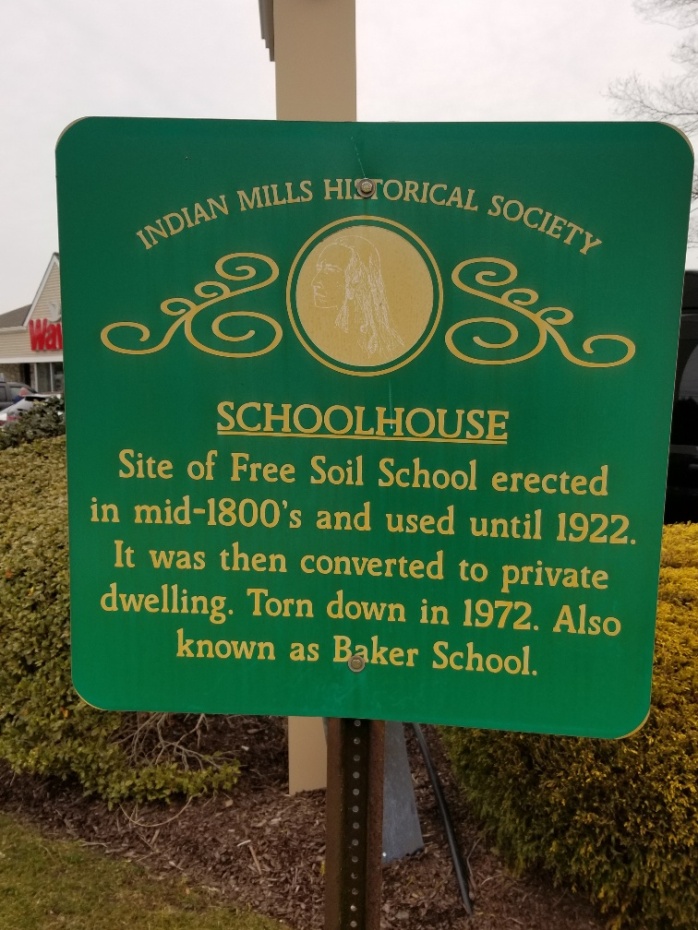

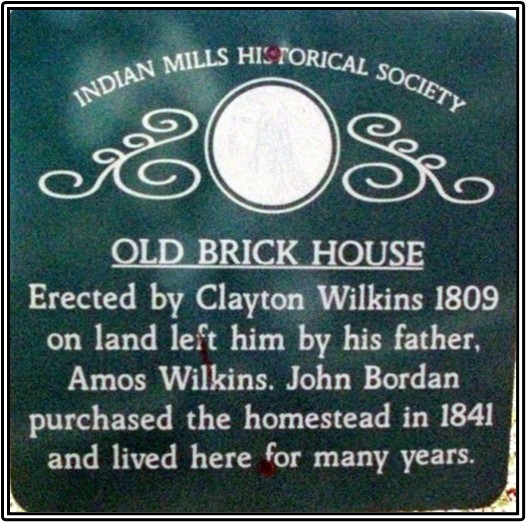

The gallery below shows off many of the signs located throughout Indian Mills. A more complete listing of local markers can be found here.

HISTORICAL MARKERS OF SHAMONG TWP.

When the Indian Mills Historical society was founded in 1973, one of the first projects on the agenda was to identify the historic sites in Shamong Township and place a marker at each location. Our historical maker program has been in place ever since, George Flemming, his son Scott, and Don Catts erected the first markers in 1975. Today there are 30 historical markers erected in Shamong Township by the Indian Mills Historical Society.

With the development of the “Shamong Township Master Plan”, twelve additional sites have been identified and our home, the Jennings house and Washington Forge below Hampton on the Batsto River should be added along with East Fruitland on Quaker Bridge Road.

The purpose of these historic markers is to acquaint today’s young people as well as the residents of Shamong Township with the unique and historic nature of the township in which they live. It is our hope that the information about the historic sites presented here will be one more step toward an increased appreciation of the township’s past and the need for future preservation of the rich historical heritage within our community.

HISTORICAL LANDMARKS

1. Flyatt 2. Stage Road 3. Still Family 4. Small’s Hotel 5. Schoolhouse 6. Shamong Trail 7. Old Brick House 8. Braddock’s Folly 9. Sign of the Buck 10. Dellett 11. Treaty Tree 12. Congressman 13. Red Men’s Hall 14. Hartford School 15. Merchant 16. Meeting House 17. Sawmill 18. Brainerd 19. Country Store 20. Church 21. Thompson Home 22. Bedford Mills 23. Indian 24. Atsion Church & Cemetery 25. Pic-A-Lilli Inn 26. First Fire Station 27. Indian Mills Elementary 28. Historic Sites 29. Wharton 30. Reservation Boundary, 31. Jennings House 32. Still Burial Ground 33. Indian Burial Ground 34. Gate Tavern 35. Hampton (Forge) 36. Cline’s Tavern 37. Little Mill 38. Catholic Burial Ground 39. Ice House. 40. William. 41. Washington Forge 42. East Fruitland 43. Willow Grove Farm 44. Charter School 45. Naylor’s Corner

IMHS Historical Marker #1 Flyatt (Intersection of Oakshade and Tuckerton Road) by Don Catts

Little is known about Flyatt prior to John King opening the “Half Moon and Seven Stars Tavern” on his 101 acre Property called the “Flyatt Planation” at the beginning on the nineteenth century. The tavern sat on the northwest corner of the intersection. There it served as a tavern, hotel, and stagecoach stop during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Taverns were an important part of the nineteenth-century Pine Barrens. They served not only as a tavern, but also a stagecoach stop and a hotel for travelers. Often the tavern house was home for the tavern keeper and his family. The Half Moon and Sevens Stars tavern house also served as home for John King, his wife Margaret, and their ten children.

A small settlement sprang up around the tavern called “Fliatum”, sometimes spelled “Flayatem”, later shortened to “Flyatt”. The tavern linked this isolated settlement to the outer world. It was a place where strangers could learn of the place they were in, while the locals heard the news of the outside world. It served as a social center where folk could meet their neighbors for conversation.

Excerpt from an article in the Mount Holly newspaper around 1870 ….

Flyatt and Atsion the former in the northern part, and the latter in the southwest part, near Fruitland, are small thriving little places in Shamong Township.

The area became a thriving community, but like so many small settlements in the Pine Barrens, it only flourished for a short time. Although the settlement no longer exists, the name Flyatt remains on some of today’s maps.

John King operated the tavern/hotel on the Plantation, until his death on March 25, 1813. Reuben Lewallen continued to operate the tavern until 1815, then Amos Troth until 1818 when Isaac Lewallen bought the 101 acre tavern plantation on June 13, 1818. By 1820 it was called the Flayatem Hotel.

An advertisement in the New Jersey Mirror newspaper …..

Sheriff’s sale to be held on Saturday November 23, 1820 at the house of Samuel Swain, Innkeeper in Washington Township, Burlington County. All that Tavern house and plantation, situated in Evesham Township, Burlington County containing 101 acres. Commonly called Flayatem. Seized as the property of Isaac Lewallen and taken in execution at the suit of Joshua Stokes, Edmund Darnell, and William Sharp, Jr. To be sold by Samuel Haines, Sheriff.

In 1836, Mahlon Pettit applied for a license to keep a public house, inn or tavern at the Flayatem Hotel on a public road leading from Medford to Tuckerton, a place where an inn or public house has been kept for a number of years past.

On March 4, 1839, Mahlon Pettit bought the property from the Administrators of Isaac Lewallen. At this time, the Flyatt Plantation property was reduced to 71.82 acres and the tavern was called the Flyatt Tavern.

On March 16, 1879 John Henry Clay Jennings bought the property from administrators of Mahlon Pettit. By this time, the property was only 20.97 acres on the north side of Tuckerton Road. Jennings is credited as being the last person to occupy the tavern house. However, there is no record of John H. C. Jennings having ever lived in the tavern house. He lived in a small farmhouse across Oak Shade Road. The farmhouse is still there today and owned by the Indian Mills Historical Society.

John H. C. Jennings owned the tavern property until 1886 when he turned over ownership to his wife, Sarah Ann Jennings. Sarah Ann died in 1920. The property remained with her executors until March 2, 1942 when Joseph Wilks Booth Jennings, her oldest son and last living executor sold it to Jerome Stevenson Jennings for $1000. It is not known when, but by this time the tavern house had burned down. Wayne L. Jennings took possession of the property by last will and testament of his father Jerome Stevenson Jennings. On November 5, 2002, Wayne L. Jennings sold the Flyatt Tavern property to Clarence Reichenbach, he in turn sold it on March 26, 2019 to Deb & Steve Management LLC, the present owner.

An entry in the MARTHA FURNACE DIARY, PAGE 8 The diary tells us much, yet not enough to satisfy us. The diarist is mute about personal happenings at the ironmaster’s house. We must search other records. For instance; why no mention is made of the death of John King, a friend of Evans, is a mystery. King was a carter at Martha and owner and operator of the Half Moon Tavern at Flyatt. King died on March 25, 1813. He left eight children under 14 and three over that age. Evans and Joseph Doron were court-appointed guardians. Jesse and Lucy Ann took into their home the four youngest children, John, less than a year old, Lucy about 2, Margaret 4, and Mary 5. One of these children would figure prominently in the later years of Jesse Evans.

Historical Marker #2. Stage Road ( Tuckerton Road) – By Mr. Don Catts

Before Europeans arrived, the Tuckerton Road was just an Indian path called the Manahawkin Trail. It was used by the Lenni Lenape Indian tribes living near what is now Camden County for their annual summer migrations, through the Pine Barrens to the shore at Tuckerton for fishing and clamming. The first Europeans that settled here followed this same path on foot and horseback from Camden to Tuckerton. This Indian path through the Pine Barrens gradually became a crude sandy road used by wagon and stagecoach.

Stagecoach stops, inns, and taverns were established along the route at convenient distances. Travel between Philadelphia and Tuckerton would be difficult, if not impossible, without these stage stops. They were an important part of the transportation process, as they were used to change horse teams and the feeding and lodging of travelers.

This was a popular trip. In those days it was believed that bathing in the salt water would cure many ailments. On a typical trip, passengers from Philadelphia in route to the Jersey Shore would cross the Delaware River on the Cooper’s Point Ferry to Camden where they boarded a stagecoach for the two day trip to Tuckerton.

After leaving Cooper’s Point in the early morning, the stagecoach, traveling at average speeds of about six miles per hour would reach the Ellisburg Hotel in a little over an hour, where it made its first stop. The next stop was at one of the hotels in Marlton. Continuing on, once past the Old Marlton Pike cutoff the Tuckerton Road was now mostly sand and the horses slowed down to a walk, around 2 to 4 miles per hour.

The next stop was the Flyatt Hotel, in Shamong for dinner and a rest while the horses were feed and a new team hitched up. Continuing the journey, the next stop was Hampton Gate Tavern also in Shamong, and then on to Washington Hotel deep in the Pine Barrens of Washington Township, the last stop of the day.

The next morning there was one more stop at Bodine’s Tavern on the Wading River then on to Tuckerton.

The Tuckerton Road follows basically the same route today. However, a 4×4 vehicle may be needed to get through some areas of the Pine Barrens.

Historical Marker #3 – Still Family – By Mr. Don Catts

Levin and his family lived on the sawmill property for about one year, at which time, on April 9, 1812, their son James “The Black Doctor of the Pines” was born. From there they moved to a place about one mile away, called the Thompson place where they spent one year. From Thompson’s, they moved in with an old colored man by the name of Cato. After living with Cato one or two years, they bought some land from him and built their homestead house on it. It was a log house, with one door and no glass windows.

All of the Still men were wood choppers. James chopped wood until the age of 18, at which time he was bound out to the Wilkins farm in Fostertown for a term of three years. James was to have three months schooling, one month each winter. His entire education consisted of these three months.

Without any medical credentials, he became a self-taught herbalist and homeopathic healer. There is no written record of him learning the herbal medicine he produced and used in his practice from Native Americans. No records remain from Still’s practice; the only source that identifies the herbs and plants he used is in his autobiography. Anything beyond the ingredients contained in his book is speculation.

The doctor became one of the wealthiest men in the area at the time and the third largest real estate owner in Medford Township.

In response to his success, local doctors challenged his medical credentials. But, because he never claimed to be an MD, nor ask for a fee for his services, there was no legal action.

Still married Angelina Willow on July 25, 1835 and the couple had a girl, Beulah. Angelina died from tuberculosis in August 1838, and young Beulah died in August 1839. Angelina and Beulah are buried in the Still Cemetery across Stokes Road from the Still Homestead in Shamong. On August 8, 1839 James married his second wife Henrietta Thomas. Together they had seven children: James Jr, Joseph, Angelina, Lucretia, William, Emeretta, Elizabeth Ann.

James Jr. graduated from Harvard Medical School with honors in 1871. Son Joseph sustained his father’s legacy, serving as an herbalist in Medford and later Mount Holly

In 1877, he published his autobiography, Early Recollections and Life of Dr. James Still. Five years later, in 1882, James Still died of a stroke at his New Jersey home and was buried in the churchyard of Jacob’s Chapel in Mt. Laurel, NJ.

James Still wrote in his autobiography …..

I had a great love for truthfulness, and was very fearful of the devil and ghosts, particularly at night. I was also afraid of Indian Job. He was a tall man; I think six feet and six inches, high. He would often get drunk, and go whooping about in Indian fashion, which was a great terror to me. Job was killed finally. A wagon containing a cord and a quarter of green oak wood passed over him in one of his drunken frolics. I was at first elated at this, but afterwards came to consider that a dead man or a ghost would be more difficult to evade than a living one. The matter so disturbed me that at night I scarcely dare stir from the house for fear of seeing him.

There is much more information about Dr. James Still at his

Historic Office Site and Education Center at 211 Church Road, Medford, NJ 08055.

William married Letitia George in 1847 and together the couple had four children: Caroline Matilda Still, one of the first African American women doctors in the United States; William Wilberforce Still, a prominent African American lawyer in Philadelphia; Robert George Still, a journalist and print shop owner; and Frances Ellen Still, an educator who was named after the poet Frances Watkins Harper.

William was an abolitionist, conductor on the Underground Railroad, businessman, writer, historian and civil rights activist. As a successful businessman, he purchased real estate and also opened a coal yard in 1861. But, he is best known for his self-published book “The Underground Railroad” in 1872. William Still died on July 16, 1902 in Philadelphia, Pa.

Soon after Charity’s escape, Peter and Levin Jr. were sold to a plantation in Kentucky. From there the brothers were eventually sold to a slave-owning family in Alabama. It was there that Peter met and married Lavinia (Vina) Sisson, a household slave from a nearby plantation. Peter and Vina had three children Peter, Levin, and Catharine. In 1831, Peter’s only family, Levin died.

Through a verbal arrangement, Peter secured his freedom in April 1850. Soon Peter arrived in Philadelphia and was directed to the Anti-Slavery Office, where he met his younger brother William for the first time. He tells William about wanting to reunite with his family. Through his own efforts, and those of his family, Peter was eventually reunited with his wife and children in 1854. His biography is documented in the book “The kidnapped And The Ransomed”, the personal recollections of Peter Still and his wife Vina, after forty years of slavery, in 1856. They resided in Burlington County, NJ until Peter died of pneumonia in 1868.

IMHS Historical Marker #4 – Small’s Hotel – by Don Catts

(Intersection of Oakshade and Indian Mills Road)

Call it the old “Small’s Tavern”, call it the “Tumble Inn” or call it “La Campagnalia” all would be correct. This building has been operating as a tavern continuously since 1830, with the exception of prohibition.

The Small family was among the earliest settlers at Indian Mills. Israel Small, a farmer, settled in present day Shamong Township in 1800. In 1818, he purchased 64 acres on the southwestern corner of the intersection of Indian Mills Road and Oak Shade Road from the estate of John King. On the corner of the intersection he built a large farm house for himself, his wife Mary, and their ten children.

In 1830, Israel converted his farmhouse into a hotel called Small’s Hotel & Tavern.

The tavern soon became a very popular gathering place for hunters, travelers, farmers, and local residents. Like most taverns in those days, a small settlements grew up around it. The town committee held meetings, general elections, and local auctions in the tavern.

Israel Small operated the hotel & tavern until 1850 then he turned over ownership to his son Benjamin who changed the name to Small’s Inn.

At a sheriff sale on April 19, 1879, Thomas Crain purchased the tavern property. Crain ran the business for a couple of years before renting the old tavern house to Dora Small who carried on the business.

In 1898, William E. Haines purchased the farm and tavern house from the estate of Thomas Crain. The Hotel was in the Haines family for one year. In Dec 1899, William E. Haines and his wife Tracy sold it to David Sharp of Mansfield, N.J. George W. Baker and his wife Hannah of Evesham Township were the next to purchase the hotel property in 1904.They changed the name to Baker’s Hotel. George was a religious man and soon became very popular in the community. Once again the tavern room was used regularly for elections, town meetings and public auctions.

Prohibition closed Baker’s tavern in 1919, and three years later, in 1922, he sold out to Mr. and Mrs. Carter of Pennsylvania, who in turn sold the building and property to Charles and Mamie Jennings in 1930. Jennings changed the name to “Tumble Inn” and continued to operate the tavern until the 1960s when it was sold.

Sometime in the 1970’s the new owner renovated the building and added a large dining room. They also tore down the out buildings and carriage sheds behind the tavern house. After going through a couple more owners and name changes such as “The Countryside Inn”, today it is owned by D.G. SPARACIO PROPERTIES, LLC and operates under the name of “La Campagnalia”.

IMHS Historical Marker #5 – Schoolhouse – by Don Catts

In the mid 1800’s, John Crain donated land on the southeastern corner of Indian Mills Road and Oakshade Road for a Schoolhouse. A one room schoolhouse was built and was named Free Soil School. The “Free Soil Party” was a short-lived political party and the forerunner of the Republican party active from 1848 to 1854, at the time the school was built. Sometime after George Baker bought the Tavern/Hotel on the northeast corner the school was called the Baker school.

The Free Soil/Baker School served the Burlington County School district #91 in Shamong Township until 1922, when the Indian Mills Elementary School was built and Shamong consolidated their five school districts.

The building was sold at public sale in 1922 to Vernon Drayton. Drayton converted it into a private dwelling and lived there for many years. It was later abandoned and stood vacant until the late1970’s when the Indian Mills Fire Company burned it down as part of a fire drill.

From the township school records, some of the school teachers were: Hannah Taylor (1900), Nellie Stokes (1906), Julia Gaskill (1907), Norbert F. Diesch (1914), Maud A Smyth (1917). This picture (no date) was taken from the La Campagnola Restaurant corner. The gravel road is Indian Mills Road and the gravel road to the left is Oak Shade Road. The schoolhouse sat where the WaWa is today.

Historical Marker #6 – The Shamong Trail – by Don Catts

(Stokes Road in Shamong is part of the Trail)

The Shamong Trail was an old Indian path that traversed what later became Burlington County. Several of Burlington County’s paved roadways today originated as Indian paths. One such road was Route 541, which was originally the northern half of the Shamong Indian Trail. When Europeans arrived to this region it was occupied by the Lenape Indian (Delaware) tribes, who had lived in the area for several thousand years. The Lenape established an extensive network of trails through the Pine Barrens of South Jersey to facilitate seasonal migrations to the coast. Most trails were only about 2 or 3 feet wide, enough for one person on foot or horseback.

The Leni-Lenape Indian tribes from the Burlington City area of Burlington County used the Shamong Trail for their annual migration to the Coast for fishing and clamming.

The trail was traveled by early European settlers who cleared and widened it into a crude road to accommodate their wagons and Ox carts. Over the years the road was improved several times. Eventually, with the coming of the automobile the road was widened and graded. Today the northern section of the Shamong trail is known as Route 541 for some 25 miles from Burlington City to Route 206 in Shamong Township.

Beginning in Burlington City, the Shamong Trail (Route 541) headed southeastward through Mount Holly and down the Main Street of Lumberton and Fostertown. From Fostertown to Medford, the trail is today’s Medford-Mt. Holly Road (Route 541). Between Lumberton and Medford, the winding trail was straightened for automobiles during the road construction.

Through Medford, it is Main Street. Leaving Medford, the trail which is now Stokes Road continues another 3 miles until it reaches Medford Lakes. Two hundred years ago, Medford Lakes was the small ironworks town called Edna Furnace. This seems to have been a popular campsite for the Lenape; there have been many Indian artifacts found here over the years. Through Medford Lakes, Stokes Road was called Mountain Run Road after a little stream of the same name that ran into the Lakes.

After leaving Medford Lakes, the trail continued down today’s Stokes Road (Route 541), crossing the Manahawkin Trail (the Old Tuckerton Stage Road) at five points where Shamong Township begins. The trail followed today’s Stokes Road through Shamong to Route 206, then down to the Mullica River at Atsion. The intersection of Willow Grove Road and Stokes Road in Shamong Township must have been another popular resting place or campsite for the Indians. A large number of Indian artifacts have been found in this area, also.

Upon reaching Atsion, apparently the path spit. One trail followed the Mullica River down to the Great bay and on to the ocean. These Indians followed the river to take advantage of the good fishing, especially in the spring when the shad and herring were making their run up the river to lay their eggs in the fresh water. But the main trail continued in a southerly direction, the destination was Cape May.

Historical Marker #7 – Old Brick House by Don Cattts

(formally located on Oakshade Road)

There is little to be said about Historical Marker #7, the Old Brick House. Clayton Wilkins built the brick house in 1809, on the farm he inherited from his father, Amos Wilkins. It was sold to John Sorden in 1841. And at one time it was owned by Charles Braddock. In 1943, Lewis Schrider purchased the farm property. Today the house is gone and the property is part of the Abrams Homestead LLC.

The historical marker was placed in front of the old brick house because it was one of the oldest houses in Shamong. The first brick house built in the township, it’s all red brick construction was unique. This was my favorite house when I moved to Shamong in 1971. I was in it several time.

IMHS Historical Marker #8 – Braddock’s Folly by Don Catts

“Braddocks Folly” William Roger Braddock, a judge from Medford, purchased large tracts of land on both the north and south side of Atsion Road. One tract on the north side included a large meadow, known as “Sorden’s Meadow”. Cultivating cranberries was unheard of at the time. In 1850, when Braddock attempted to cultivate cranberries in Sorden’s Meadow, the meadow became known as “Braddock Folly.” However, he was very successful and is credited as being the first in the area to produce cultivated cranberries.

After 170 years, Braddock’s bogs on the south side of Atsion Road are still producing cranberries, under the ownership of Frederick O. Miller of the “Dutchtown Farms Inc.”

The Ruby of the Bogs, the Cranberry is one of only three fruits native to North America. The others two are Blueberries and Concord Grapes. The New Jersey Pinelands is one of the few places where cranberries grow naturally. They grow on vines which are very close to the ground. They need sandy, acidic soil with a high water table. This wet area is called a bog. Before the first Europeans arrived, the Indians not only ate cranberries, but also used them as medicine and clothing dye. The Indians of New Jersey called the berry “sasemineash“ (very sour berry). German and Dutch settlers gave them the name “crane berry” because its pink blossom reminded them of the head of a Sandhill Crane. Over the years the name was shortened to cranberry.

In New Jersey, cranberry farming began in 1835 in a bog near Burrs’ Mills in Burlington County. It was not until the 1850s that cultivation was successful and the cranberry industry boomed. Some of New Jersey’s first cranberry farms are still operating today.

In the old days the harvest began when most of the cranberries took on their characteristic ruby red hue, sometime in early October. Harvesting in those days was a long, hard job requiring many workers who picked berries by hand.

Children were allowed to miss school in order to help their families collet the cranberries.

The Thanksgiving without Cranberries: In 1959, the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare announced that some of the 1959 crop was tainted with the herbicide aminotriazole. The market for cranberries collapsed and growers lost millions. No one had cranberries with Thanksgiving dinner that year. The cranberry industry bounced back, however, with the farmers being extremely careful about their use of pesticides.

A fresh cranberry will bounce, due to a pocket of air inside, which is also why they float.

In Cassville, Jackson Township, Ocean County, John “Old Peg Leg” Webb is credited with finding the way to sort cranberries. As the story goes, because he had one leg, Webb was unable to carry the berries down his storage-loft stairs. He tripped, dumping the barrel and sending the berries down the steps. He noticed that only the freshest berries bounced all the way down to the floor. The inferior, or spoiled berries remained on the stairs where they fell. He realized then that the berry’s bounce ability was the perfect test to separate the good from the bad.

Webb’s discovery eventually led to the creation of a machine called the cranberry separator, which separates the bouncing (good) berries from the non-bouncing (poor) ones. This bounce technique was used later in Hayden cranberry separators to separate the berries into three containers best, seconds, and rejected or worthless berries. On the left is an antique Hayden cranberry separator, Patented November 28, 1905. It was used many years ago on the “The Dutchtown Farms”, a family farm owned by Frederick O. Miller of Shamong. It still works, but of course they use more modern equipment today. On the right, is a diagram of how the cranberries travel through a typical cranberry separator.

Berries from the field are poured into the hopper above a series of four inclined bounce boards. Each bounce board has a separating-board or jump, in front of it. The berries slowly drop onto the first bounce board then continue down a series of three more bounce boards. If the berries are sound when they hit the boards they will bounce over the jump and funnel into a collecting boxes for sound cranberries. They have four chances to bounce over the jump. The berries that don’t make the jump but are still good make their way down to the collecting box for seconds. The soft or rotten berries roll or slide their way down into the box for unsalable berries.

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 1876 EDWARD BUZBY, SHAMONG, NJ

Filed Jan 11 1876, all whom it may concern Be it known that I EDWARD BUZBY of Shamong in the county of Burlington and State of New Jersey have invented certain new and useful Improvements in Cranberry Separators and I do hereby declare that the following is a full clear and exact description of the same reference being had to the accompanying drawing which forms part of this specification.

The concept of the old cranberry separator is still used today.

IMHS Historical Marker #9 – Sign of the Buck by Mr. Don Catts

Under Josiah Smith’s ownership, on one of the tavern license applications he wrote the “Sign of the Buck, more commonly known as Pipers Tavern.” This was the only time that the tavern has ever been referred to as the Sign of the Buck. On all the old maps and historic records it is either referred to as Piper’s Tavern or later as Smith’s Tavern. Therefore, a more appropriate name for the historical marker may have been Piper’s Tavern or Smith’s Tavern.

In 1791, John Piper purchased a 53 acres tract of land on the northeast corner of Atsion Road and Oakshade Road from Jonathan Oliphant and his wife. Two years later, he opened a tavern called Piper’s Tavern. Being located on a busy stagecoach route, the tavern proved very successful. Town meetings, auctions, and general sales were often held at the tavern. In 1802, when the Brotherton Indian Reservation was sold off in approximately 100 acre lots, the auction was held at John Piper’s Tavern.

John operated “Piper’s Tavern” until his death in 1807. His widow Martha continued to operate it until 1811, then William Emley ran it until Josiah Smith purchased the tavern property in1822 and renamed it “Smith’s Tavern.”

Josiah Smith enjoyed the same success that Piper had with the tavern. He operated it until his death in 1855, at which time his son John and daughter Mary Ann took possession of the tavern and property. They continued to operate the tavern under the name of Smith’s Tavern.

Manassess Dellett bought John’s undivided one half of the tavern and property. He soon petitioned the court to divide the property and tavern into two equal parts. The court declined his request and ordered the entire property to be sold at public auction. Manassess Dellett bought the property in 1862 and renamed the tavern “Dellett’s Inn.

It eventually passed down to their son, Fremont Patterson. Fremont died in 1935 and his widow Delilah (nee Kell) and her children ran the hotel for several years but eventually Patterson’s Hotel closed. The building was rented out as a private home for a few years, but as time passed it became neglected and finally abandoned. It was demolished in 1975. Although Dellett was never a settlement of any kind, the name still remains on today’s maps. Some of the older historic maps have Smith’s Tavern and the real old maps say Pipers Tavern.

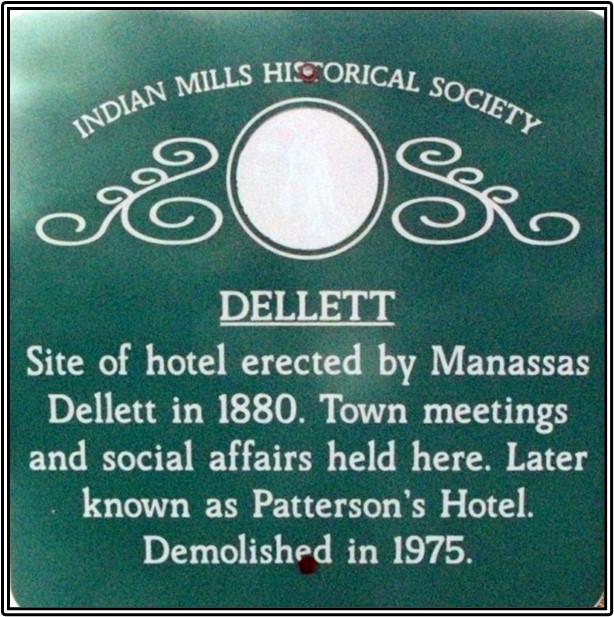

Historical Marker #10 – Dellet by Don Catts

In 1862, Manassess Dellett bought the old Smith’s Tavern (Sign of the Buck) on the northeast corner of the Atsion Road and Oakshade Road intersection and changed the name to Dellett’s Inn. He already owned a large farm and a grocery store just across Oakshade Road. Manassess farmed the land and ran the grocery store, while his oldest son Thomas operated the Inn. Thomas died in 1879 and soon after Manassess tore down the old Dellett’s Hotel/Inn on the northeast corner and erected a new Inn, across Atsion Road, on the southeast corner of the intersection. The new Inn continued to operate under the name Dellett’s Inn.

With a dance hall on the second floor and a new barroom on the first floor, the Inn was more popular than ever. It was frequently used for township meetings, dances, wedding, and other social affairs.

Deep in the Pine Barrens of southern Shamong Township, there is a small body of water known as “Mannis’ Duck Pond”. Manassess Dellett, or Mannis as he was known, had a passion for duck hunting. During the duck hunting season, he could be found at his favorite place, this small pond deep in the backwoods. He hunted there so often that local folks started calling it Mannis’ duck pond. Although he had nothing to do with the pond or the area, it became known as Mannis Duck Pond. On today’s maps it is still called Mannis Duck Pond.

Manassess Dellett died March 22, 1893 and the Hotel/Inn passed down to his daughter Anna Belle who had married Alfred H. Patterson. The Dellett Hotel/Inn was renamed Patterson’s Hotel.

It eventually passed down to their son, Fremont Patterson. Fremont died in 1935 and his widow Delilah (nee Kell) and her children ran the hotel for several years but eventually Patterson’s Hotel closed. The building was rented out as a private home for a few years, but as time passed it became neglected and finally abandoned. It was demolished in 1975. Although Dellett was never a settlement of any kind, the name still remains on today’s maps. Some of the older historic maps have Smith’s Tavern and the real old maps say Pipers Tavern.

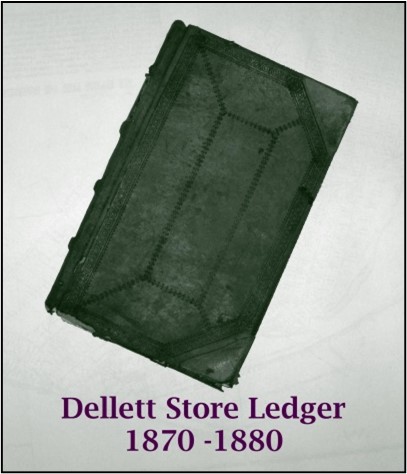

“THE DELLETT STORE” from the “Memoirs of Frederick D. (Fritz) Miller”

This is the store ledger from Manasas Delletts store located about three quarters of a mile from Dellett’s Corner (location) intersection of Atsion and Jackson Road. It stood across the road from the old brick house about 60 yds. from the road. It was one room about fourteen by sixteen with a cellar about one half underground. My father told me the cellar wall was lined with large barrels called (Hog heads) that is where he stored and cured the pork. First a layer of course salt then a layer of pork until the hogs head was about three quarters full. Then a brine was made of coarse salt and water until the brine was salty enough to float a white potato then the pork was completely covered, it was kept there until it was sold. It was common for Mr. Dellett to kill twenty hogs at a killing. My uncle Alfred Baker Miller lived on the farm in later years and I used to go in the old store.

Reading the store ledger, you can see where some of the pork went; also that Dellett was quite a business man.

This is a typical annual hog killing in early Shamong. This one is on the farm of Henry Wright.

Historical Marker #11 – Treaty Tree by Don Catts

The Treaty Tree was a large Mulberry Tree that stood in a meadow on the Gardner Farm.

In 1902, Congressman John James Gardner of Atlantic City, purchased a large farm on Stokes Road in Shamong Township and with it came one of the classic legends of Shamong. Standing in the meadow was a large Mulberry Tree.

The Legend passed down by the old folks of Shamong has it that the Indians of the old Brotherton Reservation met and sign treaties under this Mulberry Tree, giving it the title “Treaty Tree”. With no written documentation or record to prove this, it would have to be called the “Legend of the Treaty Tree”. As a rule of thumb, when the legend becomes bigger than the facts, print the legend.

After the Treaty Tree died Frederick D. (Fritz) Miller had the foresight to get a souvenir from the treaty tree. Along with some friends, Fritz got permission to cut off a small portion.

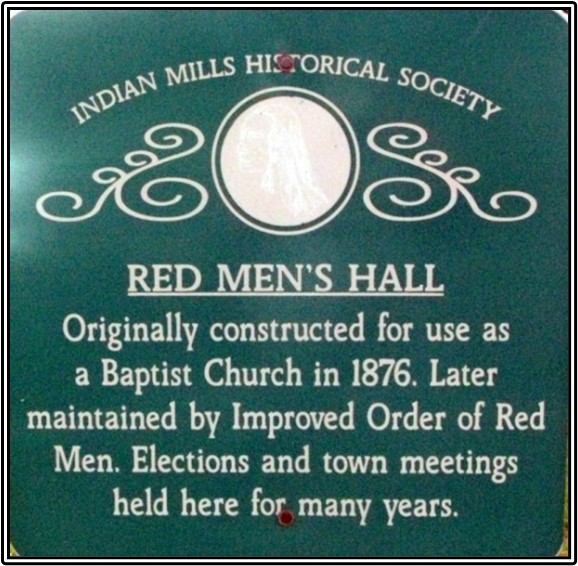

Historical Marker #13 – Red Mens Hall by Don Catts

Located at the corner of Willow Grove and Stokes Road, across from the Shamong Township Building.

Centennial Baptist Church /Red Men’s Hall constructed in 1876.

Before the construction of the Baptist Church, the Reverend Elijah Brant organized services at the Hartford Schoolhouse on School House Lane. Funds were appropriated and a Baptist Church was erected at the intersection of Stokes Road and Willow Grove Road. It opened in 1876, the year of the nation’s 100th anniversary and became known as the Centennial Baptist Church.

From the Mt. Holly newspaper in 1876:

The Centennial Baptist Church opened for religious services on March 16, 1876. Although the day was stormy, a congregation of 125 persons assembled to listen to a sermon by the Rev. Mr. Lung of Camden. Subscriptions and collections were taken in, amounting to $225. This meetinghouse is one of the neatest and prettiest small meetinghouses that is to be found in the county. Shamong is improving and someday it will be a very beautiful and important township in the county.

Apparently the church ran into financial difficulty early. By 1881, their Building & Loan mortgage of $1,400 was in default and services were no longer being held. In March 1892, James M. Armstrong of Indian Mills purchased the property at a sheriff sale. Tribe #168 Improved Order of Red Men was organized in Indian Mills in 1891and was already using the church for their meetings when Armstrong took possession. The first member, William Howard Weeks, a farmer of Indian Mills was recorded on June 25, 1891.

The Improved Order of Red Men is a non-profit, national fraternal organization, chartered by Congress. It is the oldest fraternity in the country, originating in 1765 to promote Liberty and defy the tyranny of the English Crown. The Red Men patterned themselves after the great Iroquois Confederacy, its democratic governing body and their system of elected representatives to govern tribal councils.

About 1812, the name was changed from “The Red Men” to “Society of Red Men” and in 1834 to “Improved Order of Red Men”. They kept the customs and terminology of Native Americans as a basic part of the fraternity, believing in Freedom, Friendship, and Charity.

The Indian Mills Charter, Tribe #168 Improved Order of Red Men met continually from 1891 until 1929. After 1929, there is no known documentation of meetings until 1941. A set of By-Laws dated 1941, indicates the Order must have re-chartered in 1940-41. The Red Men’s Hall was sold in 1964 to Louis Schrider Jr. and the funds were held in escrow. In 1971, after a long absence, the Tribe re-formed and was re-chartered. The women’s auxiliary of the Improved Order of Red Men, the Degree of Pocahontas, Apache Council No. 173 of Indian Mills was also chartered at this time. The Tribe now met in the Indian Mills Firehouse. Edgepillock Tribe #168 Improved Order of Red Men lost its charter around 1974-75.

The National Haymakers’ Association was a side degree of the Improved Order of Red Men. In November 1878 the Improved Order of Red Men organized the National Haymakers’ Association which was its “fun” or friendship branch. The Haymakers were a very mysterious and little known organization. It is unknown why the founders of this side degree choose to model themselves after the business of haymaking. Their meeting place was called a Hayloft. Officers had titles like Collector of Straws and Guard of the Barn Door. Candidates for initiation were called “Tramps” and were overseen by a “Boss Driver”.

A petition was submitted to the State Haymakers Association of New Jersey by Alfred Wills, James J. Wills, Benjamin W. Small, Mahlon Prickett, William H. Weeks, Mahlon Cotton, George M. Bozearth, John Miller, Isaac N. B. Wright, Theodore Miller, and Harry Wright for an association under the name of Edgepillock, Assoc No. 168 ½, of Indian Mills, NJ. On May 18, 1899 this petition was approved. Their meetings were also held at the Red Men’s Hall, which they referred to as the Hayloft.

Today, “Tribe #168 Improved Order of Red Men”, the Haymakers “Edgepillock, Association No. 168 ½”, and the Improved Order of Red Men’s women’s auxiliary the “Degree of Pocahontas” Apache Council No. 173 are all defunct in Indian Mills (Shamong). Kitty Taylor donated her scarp book of the Council #173 Degree of Pocahontas, it’s on display in our show case at the Municipal Building.

Once again Red Men’s Hall was sold. In the 1970’s the Schauman family purchased the old Red Men’s Hall property and after extensively remodeling, converted it into a grocery store. In 1997, the MacDonald family purchased the property for nursery school. Today it is a private residence.

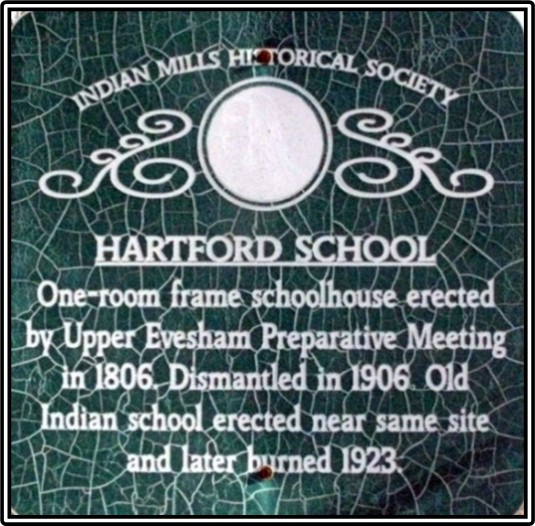

Historical Marker 14 – Hartford School by Don Catts

Before Shamong was incorporated as a Township, the area was known as Hartford. In 1805, the Upper Evesham (Medford) Preparative Meeting (Society of Friends) bought a 3 acre lot (actually 4.85 acres) at the corner of Wright’s Lane (School House Road today) and Stokes Road, on the old Brotherton Reservation. They constructed a one room school/meetinghouse facing Wright’s Lane, and called it Hartford. In the far corner of the Hartford property they laid out a cemetery.

There are no headstones or grave markers in the cemetery today. The only known burial in the Hartford Cemetery is Job Moore Sr. the father of Dr. James Still’s (The Black Doctor of the Pines) childhood friend, Job Jr.

Dr. Still wrote in his autobiography:

Job was killed finally. A wagon containing a cord and a quarter of green oak wood passed over him in one of his drunken frolics.

I recollect one night that his son Job and myself went to meeting, and as we were standing outside of the door we heard a shrill shout, which seemed to come from the graveyard where old Job was buried. Young Job said to me, “That’s daddy.” The young man’s experience, together with my own fears, was like a thousand daggers driven to my heart, and great horror seized me. I trembled in every muscle and sweat from every pore. We went into the meeting house, and I watched the door and windows, expecting to see old Job enter, but he did not come.

It wasn’t until 1852, that the town committee voted to name the proposed new township. The choices were Shamong or Hartford. Shamong won and was incorporated by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on February 19, 1852, from portions of Medford Township, Southampton Township and Washington Township.

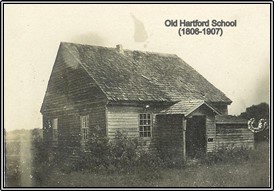

The Hartford School, the first school built in today’s Shamong Township, was in use for 100 years. In 1906, a new school house, called the Indian School, was built on the same site close to the old Hartford School. The Indian School doesn’t seem to be an appropriate name for the new school considering the Indians left the area 105 years earlier, in 1801, unless it was supposed to be called the Indian Mills School and the Mills was dropped somehow.

The new school faced Stokes Road, whereas the old Hartford School faced School House Lane. The new Indian School was opened in 1907. The following year, the old Hartford School was sold at public auction to Thomas Gardner.

The new Indian School was only in use for 15 years. In 1922, it was closed when the new Indian Mills Elementary School opened in town and all of the township school districts were consolidated into one. Lewis Schrider Sr. bought the Indian School that same year, and one year later sold it to Blair Chew for a packinghouse. Chew also bought the 4.85 acres of land where the schools sat. The old Indian School eventually burned to the ground.

Some interesting notes written by the late Frederick “Fritz” Miller (1908-1999):

My father attended the old Hartford school situated on School House Lane about seventy five yards from Stokes Road. It was one room with long benches to sit on. Their heat was from a large wood burning stove.

James Armstrong was the teacher for all eight grades, also janitor, plus cutting the wood for stove, pay one dollar a day. They all used slates instead of paper. My older brother William also attended this school in his younger days.

In 1905 the township built a new and larger school [Fritz went to this one] facing the Stokes Road yet close to the older school. One room, the seats held two pupils. Old stove close to the middle of room. There were two outside toilets. Each morning two older boys went to the creek and got a pail of water for the day. We all had our folding drinking cups but many hands went into the pail.

The house that is setting on the property today was built in 1945 and has no known historic value. However, the foundation walls in the basement are made of old brownstone that looks like they must have belonged to a much older house that sat on them at one time. It would be interesting to know the history of the original house, when it was built and who built it, etc.

Today the property is owned by a couple from Philadelphia.

IMHS Historical Marker #23 – Indian Ann by Don Catts

The legendary Ann “Indian Ann” Ashatama (1805-1894) was born about 1805. She was the daughter of Elisha Ashatama (Lashar Tamar), the last chief of the Brotherton Indian Reservation in Shamong Township. She gained fame for being the last of the Delaware Indians in New Jersey.

Ann married a black man from Virginia named John Roberts. Together, John and Ann raised seven children. They lived in a small one room log cabin on the west side of Dingletown Road (now Forked Neck Road) in a small hamlet known as Dingletown. Ann lived her entire life in Burlington County, for the most part in this small cabin on Dingletown Road (Forked Neck Road) in Shamong Township.

Ann and her husband were instrumental in the founding of an African Methodist-Episcopal Church on Carranza Road. Her husband John Roberts died young, in the Burlington County Alms House, New Lisbon, New Jersey, in 1852.

Ann was known for her fine hand woven baskets and subsisted on a meager living making basket and picking berries. Some of her basketry survives in area museums and private collections. Two are on display at the Shamong Municipal Building.

Ann’s son John Roberts Jr. enlisted in the Army during the Civil War on December 9, 1863, in Philadelphia. He served in Company A, 22nd Regiment, a US colored troop. John Jr. died of pneumonia at the post hospital in Yorktown, Virginia, less than three months after enlisting. It wasn’t until June 28, 1880, that Ann Roberts made application for a pension in regard to her deceased soldier son John Roberts Jr. It took a number of years before a small monthly pension of $8 was actually granted.

In April 1865, Ann’s son Peter purchased a 20 acres tract of land near Bears Hole Corner on Dingletown Road in Shamong Township. The purchase was made from William and Mary Cotton for $50. In June 1868, he sold the 20 acre tract to his mother Ann Roberts. In 1887, Ann was able to have a small one and a half story frame house with a cellar built on the property.

Samuel Lee Doughty, a neighbor and friend to Indian Ann, was a carpenter by trade and he built Ann’s new home. He lived just a short distance from her cabin on the opposite side of the Dingletown Road. The Doughty family must have been very friendly toward Ann Roberts for they not only gave her a mortgage on the property in the amount of $450, but Samuel Doughty went to Philadelphia and bought Ann some furniture for her new home.

Ann was known to the residents of Indian Mills as an eccentric character. She was a frequent visitor on surrounding farms and in the neighboring towns of Medford, Vincentown, and Lumberton, where she sold hand-woven baskets, brooms, and berries. Ann Roberts frequently walked to the railroad station in Medford where she would take the train to Mt. Holly to sell her baskets and other trinkets she had made. At times she was so exhausted she was unable to make the long walk home and slept overnight at the train station. In the morning she would continue her journey home. Indian Ann died at home December 10, 1894. Her remains were taken to the Tabernacle Methodist-Episcopal Church on Chatsworth Road in Tabernacle for Memorial Services. On December 13, 1894 Ann was buried in the Tabernacle cemetery in an unmarked grave. Many years after her death, the Burlington County Historical Society installed a marker indicating that she was considered to have been the last Lenape living in the county.

Indian Ann’s house is gone. It burned down in 1956. The only thing remaining today is the cellar hole and a historical marker erected by the Indian Mills Historical Society.

Nelson Burr Gaskill in 1956, gave a written eyewitness account of Ann Roberts, which best describes her in her later years: As I recall her, she was short, thick set, with a skin more brown than red, and long stringy black hair. She usually wore a man’s black felt hat and a man’s coat with man’s brogan shoes. She was a strange exotic figure to us small boys. Ann was not a neat dresser. She wore so many skirts that nothing seemed to move inside them. She was frowsy and mother insisted that she was something that rhymes with it but begins with “L” so we were ordered to keep a sanitary distance away from her. I remember that she brought little baskets woven of sweet grass and filled with teaberries.

A good friend of mine, the late Frederick Dudley “Fritz” Miller, several years ago wrote down what he knew about Indian Ann Roberts. IMHS has a copy in their files.

Ann Roberts by Frederick D. Miller

First I will tell you my source of information. My mother [Ella E. Doughty] was born in 1876, the daughter of Samuel and Selena Doughty. They lived on Dingleton Road about a third of a mile from Ann’s cabin. Ann was rather tall long black hair and smoked a pipe. Her cabin was on the edge of a small field. My mother said she heard her say several times that when she died she wanted to be buried under the large hickory nut tree that was in the middle of the field. Ann ate many meals with my mother’s family. She made baskets, round and rectangular, strapped them on her back, took them to Medford and Vincentown. Sometimes she would get the train at Medford and take them to Mount Holly. She also sold them locally.

I have one that my Grandmother told my mother that they put her in when she was first born. When mother got married her mother gave it to her.

Mother said one time she, her sister, and a small neighbor boy by the name of Atwood Wells were in the yard playing. It was almost dark. They heard someone in the woods calling. Mother ran into the house and told her father. He and Atwood’s father came out and recognized Ann’s voice. Grandfather went into the house to get a lantern. Ann called again “Mr. Wells, I want to meet you” Little Atwood grabbed his father by his leg and said “Daddy, don’t go it’s a bear and he says he wants to eat you. When they got to Ann she was on her back and could not get up. They determined that Ann had indulged in a little too much Jersey Lighting.

She had two small dogs named, “You know” and “I know”. One day a peddler came by and asked the dogs names. She told him “you know” and “I know”. The peddler remarked, you know, but I don’t know.

Ann was great for going around Indian Mills with an empty basket and going home with it full. My wife’s old maid aunt did not speak well of Ann. She described her as a dirty old beggar. She always knew when we killed hogs and came to fill her basket. Ann had a son killed in the Civil War and got a small pension from the government.

My grandfather [Samuel L. Doughty] built her house close to her old cabin a story and a half with a cellar. It burned down several years ago.